The Object Therapy exhibition opens on Friday 14 October at the Grand Stair (at Hotel Hotel in NewActon) at 6PM and will be on show until Sunday 30 October.

Object Therapy is a research and remaking project that we carried out as part of our Fix and Make program.

Through this practical study of repair we hope to build a new body of knowledge around repair, the design process, and objects and their meaning.

Often, repaired objects are perceived as being of less value. We are looking to challenge this preconception, celebrating repair as a creative process that can add value.

We hope that it will help us rethink our consumption patterns and re-evaluate the broken objects that surround us. It explores the almost forgotten role of repair in our society and its possibilities.

It’s also an enquiry into humanity. The project examines why and how we load inanimate objects with meaning.

The project has been developed in collaboration with the University of New South Wales (UNSW) the Australian National University (ANU). Through a research-based approach it is an investigation into the culture of ‘transformative’ repair as practiced by local, interstate and international artists and designers.

Back in May (2016) we did a call out to the public asking people to give us their broken or damaged objects for possible repair. From the 70 submissions, we chose 30 objects for repair including furniture items, ceramics, household appliances, textiles, sentimental objects and, unexpectedly, one human.

When they came to drop it off we interviewed each person about their object. They were asked a series of questions including how they came to own the object, how it broke and how they would like to see it repaired…

We found that some of our straightforward questions drew out personal (and sometimes quite moving) stories that highlight the power that objects have to connect us to people, places and the past. We also uncovered some attitudes towards repair and perceptions on waste.

The object owners were then asked to ‘let go’ of their objects. We let them know that the process of repair might mean that their object would come back completely different… both in terms of how it looks and functions.

We then gave each object to a design repairer. We gave them the background research as well (the video interviews) so that they could understand the owner’s relationship with the object. The repairers had six weeks to mend or transform the object.

Then we reunited the owner with their object. We did a second interview to see their response to the repair and to see if and how their attitudes or perceptions might have changed.

We are very grateful for the goodwill that the repairers have shown us by taking part in this project. They spent much time and thought on their repairs. (Thanks guys. We’re glad you’re here.)

We are also in much karmic debt to the researchers – Guy Keulemans, Andy Marks, Niklavs Rubenis and their team for all of their hard work and commitment to this project. We thank you. Believing in things is catching. We hope you infect everyone.

And thank you to the object owners for trusting us with your (almost always) beloved objects.

We have put together an exhibition of the repaired objects. It opens on Friday 14 October at the Grand Stair (at Hotel Hotel in NewActon) at 6PM and will be on show until Sunday 30 October. We hope you can come.

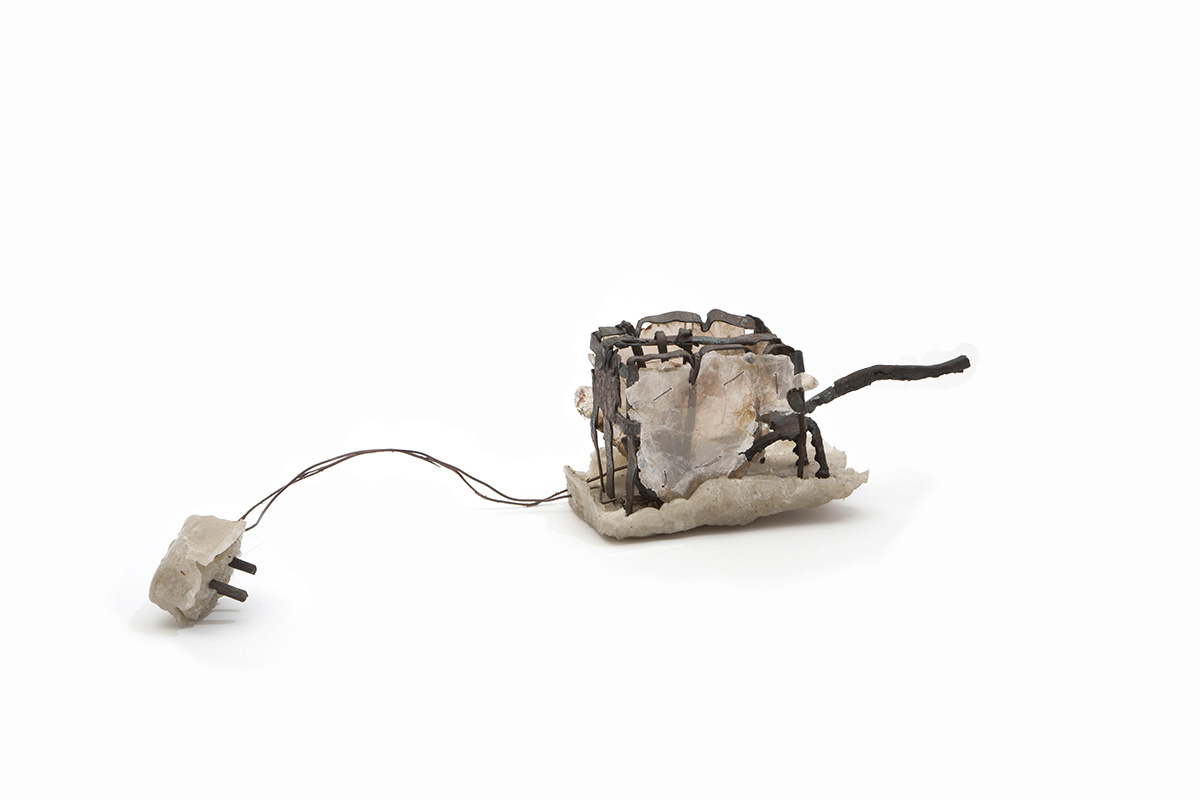

Image by Lee Grant of Kristie’s broken Kenwood mixer given to her by her parents for her 21st. Repaired by Rohan Nicol – reminiscent of an archeological artifact, he has locked the object in cement, fixing in time the often-invisible bonds between family members.

Repairers

Andrea Bandoni, São Paulo, Brazil

Corr Blimey (Louisa de Smet and Steven Wright), Cardiff Wales, UK

Susannah Bourke, Queanbeyan, Australia

Elise Cakebread, Melbourne, Australia

Franchesca Cubillo, Canberra, Australia

Elbowrkshp (Elliat Rich and James B. Young), Alice Springs, Australia

Daniel Emma, Adelaide, Australia

Dale Hardiman, Melbourne, Australia

Benja Harney, Sydney Australia

Kyoko Hashimoto, Sydney, Australia

Alison Jackson, Queanbeyan, Australia

Trent Jansen, Thirroul, Australia

Guy Keulemans, Sydney Australia

Dylan Martorell, Melbourne, Australia

Scott Mitchell, Melbourne, Australia

Liam Mugavin, Sydney, Australia

Rohan Nicol, Canberra, Australia

Monique van Nieuwland, Canberra, Australia

Yutaka Ohtaki, Murakami, Japan

Halie Rubenis, Queanbeyan, Australia

Niklavs Rubenis, Queanbeyan, Australia

SMaRT@UNSW, Sydney, Australia

Naomi Taplin, Sydney, Australia

Thought Collider (Mike Thompson and Susana Cámara Leret), Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Henry Wilson, Sydney, Australia

Richard Whiteley, Canberra, Australia.